“Oh, you’re a lawyer! Lemme ask you somethin’. . .”

Lawyers usually respond to this statement by smiling politely, nodding, and enduring the next several minutes. Occasionally the questions are novel. Occasionally the talks produce business for the attorney. One question, however, is neither novel nor productive. But that doesn’t stop nonlawyers from fantasizing about getting the inside scoop from a practicing attorney:

“What’s the best way to get out of jury duty?”

I think I get asked this question about twice a year. I always find it a bit puzzling why, somewhere within the mind of this inquisitive soul, a lawyer is the best person to ask. An attorney’s job depends upon jury duty. Even legal matters that rarely see the inside of a courtroom often depend on how juries would react if the case were presented to a jury. In that sense, it’s like asking a chef the best way to get a free meal at his restaurant, or a police officer the best way to avoid a speeding ticket. Imagine this exchange:

Inquisitive Soul: Excuse me, soldier. Thanks for your service, by the way, in defending our country and all. Um, I was wondering if I could ask you a question. I received this notice that Uncle Sam is re-instituting the draft, and I might have to join the military. Here’s the thing, though. I really don’t want to miss work. Do you have any idea how I could get out of it?

Soldier: Well, sir, I’m not sure I’m the right guy to ask.

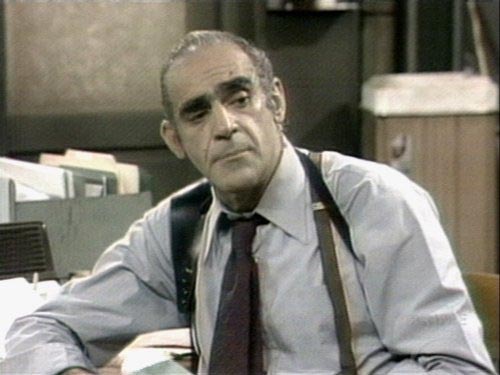

Inquisitive Soul: I know a guy that got out because he moved to Canada; and another who said he believed he was Abe Vigoda. In my case, I figure I might have a chance to get out of the draft because I have a hereditary condition that completely prevents me from being able to gargle. I know, strange, right? I’m hoping it does the trick.

Soldier: I’m going to punch you in the face now, Sir.

So why would someone want to know how to best avoid a simple civic responsibility that helps buttress society against the imminent threat of despotism and tyranny and for which the founding fathers bled and died? Alright, that’s overselling it a bit. Still, while it’s hard to imagine that jury duty is as critical to the continued existence of the republic as a standing military in a time of war, neither was it the embodiment of bureaucratic evil that it has become today.

Jury duty has been both over-glamorized and unduly feared. It is unlikely to land you a book deal or an interview with a real life reporter (or Nancy Grace). Your chances of being the center of the CNN bubble for a news cycle are slim. Listening to other people talk can be tedious. You won’t be able to text or twitter while it’s going on. Jury duty is usually devoid of the cutting edge special effects and surround sound that the American infotainment diet feeds upon. On the other hand, most who serve on juries report a more positive experience than they had expected. Most juries are not sequestered. Most trials take a couple of days, not a couple of months. The size of the commitment is typically not as onerous as many expect.

So serious is the recent increase in jury-dodging, that the Indiana Courts have put together a series of You Tube videos to help educate prospective jurors and encourage jury duty participation.

One last word of advice for the jury avoider at the proverbial cocktail party: the only person less likely than a lawyer to give you a good answer on how to get out of jury duty would be a judge. Do yourself a favor and never, ever ask a judge this question. In a recent Indiana Lawyer article, reporter Michael W. Hoskins, notes that Judge Michael Scopelitis of the St. Joseph Superior Court directed over 700 people to come to court to explain why they did not answer prospective juror questionnaires. More than 100 did not respond, and Judge Scopelitis promptly issued body attachments (essentially arrest warrants) for them. Needless to say, judges take jury duty very seriously.